When I shoot panos that include both very far and very near things, I do exactly that. When you’re dealing with pano photography, you have the option of chucking the entire hyperfocal conversation into the trash bin of history and shooting a row of frames of the ground directly in front of you with a different focus. The white point adjusted on the histogram.

#AUTOPANO GIGA DETECTING ISSUE SOFTWARE#

Software can’t correct for a poorly metered frame.ģ. The lighting can change drastically from 0° to 90°, so I sweep the camera around and meter the entire expanse before settling on a median exposure. This method is tricky, though, especially if you’re shooting a really wide pano. I shoot underexposed because it’s the best way to ensure you’re getting everything with one exposure darks can be pulled up more efficiently than blown-out whites can be recovered. I’ve had the most success locking everything down in manual: shutter, aperture, focus, ISO-everything. There are a few schools of thought on whether you should set your exposure and focus and never change them throughout the multiple frames that will comprise the final pano. Also, for a zoom, that lens is amazingly sharp. The ƒ/2.8 is a bit hefty, and the ƒ/4 with the four-stop IS is a very capable low-light, handheld landscape shooter. I chose the 70-200mm ƒ/4 IS version over the ƒ/2.8 version for weight considerations. I think a 35mm would be the perfect pano lens, and the Canon EF 35mm ƒ/1.4L is famously sharp.

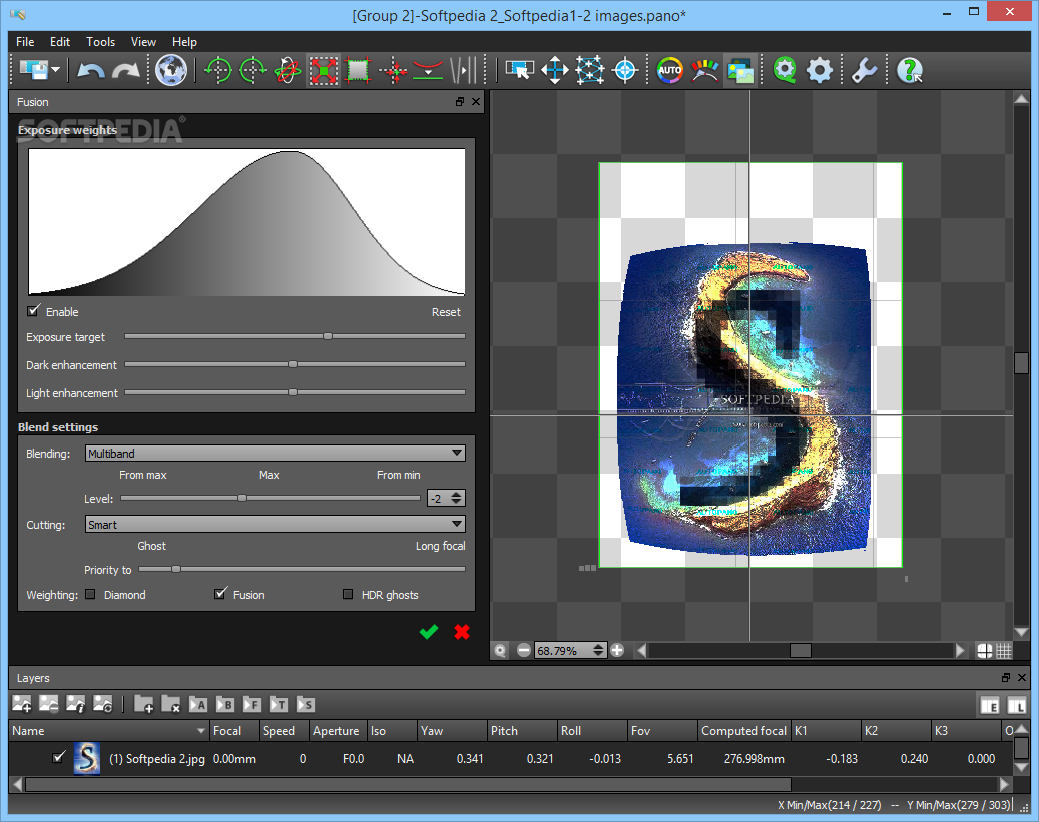

The 24mm is really pushing the lower range of focal lengths for landscape panos, but for single-shot landscapes on a full-frame sensor, it’s almost perfect. Huge peaks looming in front of you shrink into puny insignificance. It makes faraway things look small, introducing artificiality. I prefer the 50mm over the 24mm for panos due to the perspective distortion the 24mm produces. This image needs to be tonally corrected it’s still slightly underexposed, even after histogram editing in Lightroom. Note the gap in the histogram toward the highlights. I’d rather lug the weight and know that I’m holding the best tools for the job than carry a slightly lighter load and always wonder if I could be getting cleaner originals.Ģ. You’ll notice those are mostly prime lenses I do that for sharpness. That’s a lot to add to a mountaineering pack that already weighs 60 pounds, so I just train harder. I take two extra batteries and a Brunton solar charger, an Induro carbon-fiber tripod with a ballhead (the ideal combination of light and sturdy), a Kata rain cover that will accommodate all the lenses, an OP/TECH chest harness and wrist strap, a remote timer, almost 200 gigabytes of SanDisk Extreme III CF cards, Pelican waterproof CF card holders and a Brunton trek pole that doubles as a monopod with a Joby ballhead. Here’s what I carry: a Canon EOS 5D Mark II, Sigma 15mm fisheye, Canon 14mm, 24mm, 50mm prime lenses and the 70-200mm ƒ/4 IS zoom. It’s especially important to choose gear wisely when mountaineering. The RAW stitched panorama in the Autopano Giga panorama editor…looking a little dull. Here’s how it all comes together, in his own words.ġ.

He consistently chooses quality over compromise-from the gear he buys to the way he shoots. His work, above all, is meticulous and precise.

That pretty much sums up Brandon Riza’s theory about high-resolution landscape panorama photographs. Looking northeast toward Little Tahoma and the Ingraham Glacier from Cathedral Rocks, Mount Rainier, Cascade Range, Washington.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)